Monday, 2 June 2008, Into the vinyards

(Written 6 June 2008)

Monday morning, David still didn't feel 100%, and in addition he needed to practice his invited talk for the crustacean meetings in Texas next week, so he stayed in while I did the walking tour of the town (or part of it; you could spend hours). It covered many of the same things and places as the train tour, but it went into much more detail and allowed time and space for photography. Here's the plaque commemorating the 500th anniverary of Joan of Arc's success. It's outside a fine old half-timbered house that's now a museum of life in the middle ages (unfortuantely closed on Mondays; in fact, most of the museums were closed on Sunday and/or Monday, the only days we had in Reims).

Monday morning, David still didn't feel 100%, and in addition he needed to practice his invited talk for the crustacean meetings in Texas next week, so he stayed in while I did the walking tour of the town (or part of it; you could spend hours). It covered many of the same things and places as the train tour, but it went into much more detail and allowed time and space for photography. Here's the plaque commemorating the 500th anniverary of Joan of Arc's success. It's outside a fine old half-timbered house that's now a museum of life in the middle ages (unfortuantely closed on Mondays; in fact, most of the museums were closed on Sunday and/or Monday, the only days we had in Reims).

.jpg) The Carnegie library, considered the finest Art Deco building in Reims, is semicircular, with the entrance on the flat side. A bust of Andy himself stands before the door, which is decorated with mosaics.

The Carnegie library, considered the finest Art Deco building in Reims, is semicircular, with the entrance on the flat side. A bust of Andy himself stands before the door, which is decorated with mosaics.

The old covered market, considered a particularly fine one, with permanent tiled emplacements for all the stalls, was built to accommodate a city of 100,000, so Reims had long since outgrown it when it was abandoned and the city's main market moved (like Paris's) to the suburbs (though I'm told that a particularly lively weekly market takes place on a nearby esplanade). The market stood empty, and littered with the trash left there on its last active day, for many years before it was declared a national historic monument. Now it stands there, still abandoned and littered, many panes broken out of the huge semicircular windows over its doors, awaiting cleaning and restoration as a tourist attraction, as soon as the money can be raised. For now, you can only look in and take pictures through the chain-link grills that cover its entrance.

A particularly magnificent building is the original headquarters of Mumm champagnes. Its huge round doorway mimics the end of a wine barrel, and the enormous mosaics across the top show the stages of champagne making. Mumm has since moved out to the edge of town, where there's more space. I forget who's in the building now.

A particularly magnificent building is the original headquarters of Mumm champagnes. Its huge round doorway mimics the end of a wine barrel, and the enormous mosaics across the top show the stages of champagne making. Mumm has since moved out to the edge of town, where there's more space. I forget who's in the building now.

In the middle of town stands the Hotel de Ville (town hall), on its own open square and adorned over the door with this relief of Louis XIII, labeled with a plaque explaining what a good, just, powerful, and generally terrific king he was.

In the middle of town stands the Hotel de Ville (town hall), on its own open square and adorned over the door with this relief of Louis XIII, labeled with a plaque explaining what a good, just, powerful, and generally terrific king he was.

Finally, a couple of blocks away, in what used to be the middle of town, part of the old Roman forum has been excavated. I wasn't able actually to go down the steps into the ruins, because the plantings are being redone. Guys were down there ripping out a luxuriant growth of lavender, to replace it with something else, and you could smell lavender for blocks around.

I haven't mentioned half of what the tour covered, just in the half of the tour I had time for! There's a lot to see and do in Reims. On the way back to the tourism office to turn in the audioguide, I passed this particularly splended patisserie window. After turning in the guide, I bought myself a doner kabab to go (a little like a gyro), with fries, and got David a ham sandwich (something simple, at his request), and we picknicked in the hotel room before meeting our vinyard-tour guide at the door of the hotel. Because we were the only people who signed up that afternoon, we not only got to pick the language, she offered to come to the hotel rather than the usual gathering place behind the cathedral.

I haven't mentioned half of what the tour covered, just in the half of the tour I had time for! There's a lot to see and do in Reims. On the way back to the tourism office to turn in the audioguide, I passed this particularly splended patisserie window. After turning in the guide, I bought myself a doner kabab to go (a little like a gyro), with fries, and got David a ham sandwich (something simple, at his request), and we picknicked in the hotel room before meeting our vinyard-tour guide at the door of the hotel. Because we were the only people who signed up that afternoon, we not only got to pick the language, she offered to come to the hotel rather than the usual gathering place behind the cathedral.

The tour was great. Catherine is a young Russian woman who came to France for a year to learn the language, fell in love with and married a local wine-grower, and stayed on permanently. (She also travelled in Italy and the U.S. to learn Italian and English, both of which she speaks very well.) She's been in France for 7 years now, and they have a 3-year-old daughter who's in preschool (in France, children can start free public school at age 2; if the parents opt instead for a nanny, the state reimburses a part of the cost). When no one signs up for the tour, Catherine helps her husband in the vinyards. She hopes to get French citizenship in one more year. This is her first year giving winery tours; she used to work as a tour guide for Mumm, but she noticed an unmet demand for tours of the vinyards themselves and started her own business.

The tour was great. Catherine is a young Russian woman who came to France for a year to learn the language, fell in love with and married a local wine-grower, and stayed on permanently. (She also travelled in Italy and the U.S. to learn Italian and English, both of which she speaks very well.) She's been in France for 7 years now, and they have a 3-year-old daughter who's in preschool (in France, children can start free public school at age 2; if the parents opt instead for a nanny, the state reimburses a part of the cost). When no one signs up for the tour, Catherine helps her husband in the vinyards. She hopes to get French citizenship in one more year. This is her first year giving winery tours; she used to work as a tour guide for Mumm, but she noticed an unmet demand for tours of the vinyards themselves and started her own business.

Now, we're old hands at winery, champagne house, and even vinyard tours, but we still learned a lot on this tour. She started by driving us through several small villages to show us particularly nice views, the oldest champagne house in the region, and several "lavoires." The lavoires we've seen before have always been stone platforms built on the banks of rivers where the women of the village came to wash clothes, but in the Champagne region, they are stone communal laundry tubs, covered open-sided tile-roofed sheds, typically about 10 by 20 feet. Each one is fed by a spring and then drains into a stream. They're no longer used for laundry, but the water in some is actually potable, and villages tend to be very proud of them and to keep them surrounded by attractive plantings.

We visited vinyards of each of the three wine varieties used for champagne: pinot noir, which is trained horizontally on trellis wires; chardonnay, which is very fragile

and is therefore trained upright so that the vines aren't bent so sharply; and pinot meunier (literally "miller's pinot"), also trained horizontally, which gets its name from the tiny white hairs that cover its new shoots, giving them a "floury" look. You can see the effect in the photo.

We visited vinyards of each of the three wine varieties used for champagne: pinot noir, which is trained horizontally on trellis wires; chardonnay, which is very fragile

and is therefore trained upright so that the vines aren't bent so sharply; and pinot meunier (literally "miller's pinot"), also trained horizontally, which gets its name from the tiny white hairs that cover its new shoots, giving them a "floury" look. You can see the effect in the photo.

The "viticulteur," the wine-grower, prunes the vines in the winter, cutting off all of last year's growth except for a single cane, which is trimmed back to a length of about 4 axillary buds, bent sideways (unless it's chardonnay), and tied to a low trellis wire. This pruning requires expertise and is still done by hand. When we were there, the year's new growth was well under way; vigorous new vines were growing upward from the trimmed shoots tied to the wires last winter. Only these vines growing from last year's wood will bear grapes, so all the wine-growers spend their days out among the vines these days, trimming away any shoots from older wood or from the vine's stump and raising trellis wires (left lying on the ground along the rows for the purpose) so that they support the growing shoots on both sides and keep them from flopping over sideways. Once again, as far as you could see across the valley of the Marne, the vinyards were dotted with little white vans and guys in boots, clipping shoots and raising wires. When the vines have filled out and grown sufficiently tall (meaning as high as the highest trellis wires), they will also have bloomed and set their fruit (they're in bud now, and have only one trellis wire to go). At that point, those tall row-straddling tractors come in to do the routine trimming. They run along the rows using spinning blade to trim off the ends of new sprouts that extend upward or outward from the rows, thus keeping the vines' minds and resources focused on the green grapes. Finally, in the fall, all the grapes in the champagne region are still picked by hand, and each bunch is individually groomed (green or spoiled grapes removed, etc.). Apparently, temporary workers come from all over France to work during the harvest. The bunches are not stemmed; the grapes are crushed still in their clusters and very slowly and gently, so that the color from the skins is not releaed and so that no bitter juices from the stems get into the mix.

Of course, training the vines another four buds sideways along the wires every year can't go on forever; in three or four years, each vine runs into its neighbor, and they start shading each other. So every 3-4 years, the vines are cut back to the stumps and start the horizontal training process over again. Every 30-35 years, they're torn out altogether and replaced with new ones (cuttings grafted onto Phylloxera-resistant American rootstocks), because the grapes' acidity declines with increasing vine age, and you need high acid content to make champagne. Grapes from old vines are used only in pink champagne, because the skins are more strongly pigmented. The photo shows a plot of old pinot noir vines maintained by Veuve Cliquot both for pink champagne and as a source of cuttings for new plantings.

Of course, training the vines another four buds sideways along the wires every year can't go on forever; in three or four years, each vine runs into its neighbor, and they start shading each other. So every 3-4 years, the vines are cut back to the stumps and start the horizontal training process over again. Every 30-35 years, they're torn out altogether and replaced with new ones (cuttings grafted onto Phylloxera-resistant American rootstocks), because the grapes' acidity declines with increasing vine age, and you need high acid content to make champagne. Grapes from old vines are used only in pink champagne, because the skins are more strongly pigmented. The photo shows a plot of old pinot noir vines maintained by Veuve Cliquot both for pink champagne and as a source of cuttings for new plantings.

We were in the pinot meunier area, so most of the vines we saw were of that variety, but some growers make their own champagne, from grapes grown on their own land, so they need all three. In that case, chardonnay is always planted low on the hillsides (because it's also touchy about temperature) and pinot meunier near the top, because it tends to ripen earlier than the others, and the cooler temperature slow it down. (Pinot meunier is also considered the most disagreeable to work with, because in dry weather, the cottony little hairs fill the air—(and the nostrils. That wasn't a problem for us, because it rained off and on all day. ) At the bottoms of the hills, on the flats in the river valley, the alluvial soil is wrong for grapes (which need chalk), so those areas are planted in wheat and barley. Some champagne houses (like de Castellane) own no vinyards and buy all their grapes, and some growers, like Catherine's husand, make no champagne but sell their grapes to those who do. He has hundred-year contracts to sell different portions of his crop to particular champagne makers.

Along the way from stop to stop, Catherine took care to point out local curiosities, like the stones lining the road into a park, which had been carved into the shape of two-foot-high champagne corks, and all the old wagons and carts used as planters or lawn ornaments (it seems the superstition is that anyone who destroys an old cart will fall gravely ill or even die, so the carts are left to fade gradually away of their own accord). She explained that the little two-inch brown plastic capsules hanging everywhere, on trellises, on trees, wherever, emit the pheromones of female lepidopterans, the theory being that if the males are assailed on all sides by the attractants, they won't know which was to turn, fewer romantic encounters will take place, and fewer caterpillar eggs will get laid on the vines.

Up near the top of a hill, Catherine pointed out the large, brightly colored plastic bags tied onto frames at the ends of vinyard rows, each bearing a large number "8." She explained that, on hillsides that steep, the tractors are too top-heavy, so the annual spraying is done by helicopter. The "8" means "due to be sprayed in 2008" and the color and design of the bag corresponds to the helicopter company. Strolling around admiring the view, the birds, the vinyards, and the wildflowers, we viewed this chalk bank. The pine twig provides scale, and the pine's roots illustrate the way the vine's roots penetrate the chalk, following and enlarging tiny cracks and crevices. We also spotted a patch of dull olive-green soil, which we assumed had been sprayed with something to make it that color, but Catherine assured us that that's the natural color of clay in this region! There on the hill, with the vinyards in the background, she dressed us up in native costume and took our picture, David in his cloth cap and blue apron and me in my apron and sun bonnet—champagne gothic.

Up near the top of a hill, Catherine pointed out the large, brightly colored plastic bags tied onto frames at the ends of vinyard rows, each bearing a large number "8." She explained that, on hillsides that steep, the tractors are too top-heavy, so the annual spraying is done by helicopter. The "8" means "due to be sprayed in 2008" and the color and design of the bag corresponds to the helicopter company. Strolling around admiring the view, the birds, the vinyards, and the wildflowers, we viewed this chalk bank. The pine twig provides scale, and the pine's roots illustrate the way the vine's roots penetrate the chalk, following and enlarging tiny cracks and crevices. We also spotted a patch of dull olive-green soil, which we assumed had been sprayed with something to make it that color, but Catherine assured us that that's the natural color of clay in this region! There on the hill, with the vinyards in the background, she dressed us up in native costume and took our picture, David in his cloth cap and blue apron and me in my apron and sun bonnet—champagne gothic.

Finally, Catherine took us to another little village, Coulommes-La-Montagnes (dotted, as usual, with signs pointing in all directions to champagne houses), to visit a small champagne house, Ponson Père et Fils (Ponson Father and Son), that she has a standing arrangement with. It's an example of one that does everyting; they grow their own grapes, of all three varieties, then produce and sell their own champagne. They have their own equipment for most of the steps, but for the bottling step, they employ an itinerant bottling plant that travels around the region in a truck, working for different makers by appointment. Keeping the touchy workings and fiddly adjustments of a mechanical bottling line tuned and humming isn't easy, especially when you only need it three days a year, so the smaller makers bring in the specialists for that one step.

Finally, Catherine took us to another little village, Coulommes-La-Montagnes (dotted, as usual, with signs pointing in all directions to champagne houses), to visit a small champagne house, Ponson Père et Fils (Ponson Father and Son), that she has a standing arrangement with. It's an example of one that does everyting; they grow their own grapes, of all three varieties, then produce and sell their own champagne. They have their own equipment for most of the steps, but for the bottling step, they employ an itinerant bottling plant that travels around the region in a truck, working for different makers by appointment. Keeping the touchy workings and fiddly adjustments of a mechanical bottling line tuned and humming isn't easy, especially when you only need it three days a year, so the smaller makers bring in the specialists for that one step.

We toured their cellars, saw their "riddling machines" in action (the new mechanical devices that carry out—much more rapidly than humans can—the process of turning and inclining the bottles to induce the sediments to collect in the necks. They had several of the newer 100-bottles-at-a-time machines, but also a few of the original model, the "Pupi-matic" (from "pupitres" the name for the old-fashioned wooden riddling racks). They even riddle some of their single-year vintage champagne by hand.

The tour ended, of course, with a tasting, and David was delighted with the champagne, pronouncing it more to his taste than Moët-et-Chandon's Brut Imperial, hitherto his gold standard. Very toasty, apparently. So I, of course, asked "but will we be able to buy it in Tallahassee?" No, Catherine assured us; you can't even buy it in Reims. It's sold only right there, out the door of the building where it's made. That's got to be what some of those negociants and buyers are doing, driving around the countryside on behalf of restaurants and wine merchants, acquiring the products of these small, but very special, producers.

The tour ended, of course, with a tasting, and David was delighted with the champagne, pronouncing it more to his taste than Moët-et-Chandon's Brut Imperial, hitherto his gold standard. Very toasty, apparently. So I, of course, asked "but will we be able to buy it in Tallahassee?" No, Catherine assured us; you can't even buy it in Reims. It's sold only right there, out the door of the building where it's made. That's got to be what some of those negociants and buyers are doing, driving around the countryside on behalf of restaurants and wine merchants, acquiring the products of these small, but very special, producers.

This was a great tour. Check out Catherine's website at http://www.lavigneduroy.com/. We recommend her highly.

Catherine dropped us back at the hotel, and we spent a while getting the chalk, green clay, and whatnot off our shoes and cuffs—worth it, though—then changed and took a cab to the evening's restaurant, l'Assiette Champenoise in the suburb of Tinqueux for a terrific dinner.

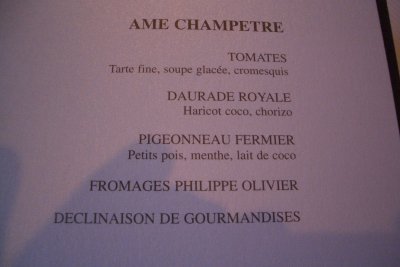

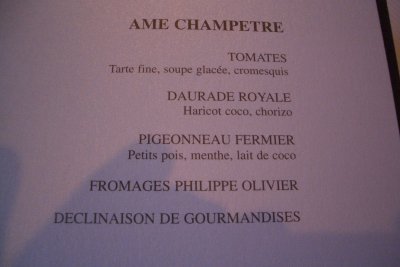

This place and the restaurant from the previous night are both GM 17/20, the two top chefs in the city, and clearly strong cross-town rivals. Once again, the table was set with both sweet and demi-sel butter, this time topped by a little label bearing the chef's name (as was, it turned out, just about anything in the place that could be labeled). The menu was deceptively simple; you can see all of it right there in the photo.

This place and the restaurant from the previous night are both GM 17/20, the two top chefs in the city, and clearly strong cross-town rivals. Once again, the table was set with both sweet and demi-sel butter, this time topped by a little label bearing the chef's name (as was, it turned out, just about anything in the place that could be labeled). The menu was deceptively simple; you can see all of it right there in the photo.

Amuse-bouch 1: A mini-panini of ham, roblochon cheese, and sucrine lettuce.

Amuse-bouche 2: Vegetables, mainly thinly sliced carrots but a few others as well "en escabeche" (sort of a vegetable seviche) topped with orange mousse so fragile and insubstantial that it shimmied on the spoon.

Amuse-bouche 2: Vegetables, mainly thinly sliced carrots but a few others as well "en escabeche" (sort of a vegetable seviche) topped with orange mousse so fragile and insubstantial that it shimmied on the spoon.

First course: Three variations on tomato: a room-temperature tomato tart with a veritable vegetable garden on top (the dark bits are eggplant, and a bit of artichoke and some asparagus ar lurking behind the mushroom), tomato ice cream/gaspacho with pesto and red piquillo chiles, and cube-shaped tomato cromesquis served in a paper cone standing in a tall conical dish of rock salt. All three were esquisite.

First course: Three variations on tomato: a room-temperature tomato tart with a veritable vegetable garden on top (the dark bits are eggplant, and a bit of artichoke and some asparagus ar lurking behind the mushroom), tomato ice cream/gaspacho with pesto and red piquillo chiles, and cube-shaped tomato cromesquis served in a paper cone standing in a tall conical dish of rock salt. All three were esquisite.

Second course: Daurade royale (roasted "sur la plancha," i.e., on a very hot surface) with both emulsified and whole summer cocos (fresh white beans) and a chorizo mousse. Everyone seems to be serving chorizo with fish these days, but it works surprisingly well. The waiter spooned a dollop of the mousse into each bowl, then left the sauceboat in case we wanted more.

Second course: Daurade royale (roasted "sur la plancha," i.e., on a very hot surface) with both emulsified and whole summer cocos (fresh white beans) and a chorizo mousse. Everyone seems to be serving chorizo with fish these days, but it works surprisingly well. The waiter spooned a dollop of the mousse into each bowl, then left the sauceboat in case we wanted more.

Third course: Rare breast of pigeon (cooked at low temperature) on a bed of puréed green peas flavored with mint and surrunded by a frothy coconut-milk sauce.

Cheese course: We both had some of a delicious, mild, creamy, dome-shaped cheese with a powdery white rind which we've had once before but can never catch the name of. David had some robolchon and some roquefort. I had a Swiss gruyère and an ashed chevre.

Mignardises: They served the mignardises before dessert, perhaps in hopes we'd actually eat some of them. They came in eight parts: A silver box with bars of strawberry and rhubarb marshmallow, accompanied by a pair of silver scissors for cutting off the amount you wanted. A different silver box containing individually wrapped cramels, nougat, and lollipops. A silver dish with eight little crispy cookies, each topped by a square of apple paste (a dead ringer in flavor for those puff-pastry apple turnovers David is so fond of). A silver basket containing two tuile cookies. A covered silver box in the sape of a seed pod containing several varieties of chocolates. A rectangular silver box containing six miniature "cannelées bordelaises" (little crispy-chewy cylindrical cakes that the French go wild over). And a silver dome with holes in it to support two puffs of cotton candy (white this time). Each of those silver dishes, baskets, boxes, etc. was heavier than you could believe for its size. There must have been 25 pounds of silver on the table, most of it bearing the chef's name.

The dessert actually involved a choice. David chose variations on chocolate; I chose variations on fruit. Each of them came in four dishes.

Dessert, David: A square of dark chocolate ganache topped with a quenelle of outstanding macadamia-nut ice cream. A cylinder of hazelnut-flavored chocolate onto the center of which the waiter poured a thin stream of hot coffee sauce until the sauce drilled a hole through the cylinder. A martini glass containing a cube of white chocolate with pistachios in and on it, surrounded by a white foamy sauce. A second martini glass full of Coca Cola sorbet sprinkled with chunks of chocolate cookie and topped with a creamy white foam.

Dessert, me: A martini glass of fresh strawberries in a soft strawberry gel topped with foamed milk and a sprinkle of pink candy crumbles. A dish of poached rhubarb spears, each paralleled by a strip of peach sorbet, and sprinkled with bits of orange peel (?) and bits of cookie crumble (Reims's famous pink macaroons?); the waiter poured a pale-pink liquid around it at the table (pink champagne?). A thin, crisp sheet of pistachio brittle formed into a tube, square in cross section, and filled with wild strawberries and cream brulée. A small clafouti of fresh cherries (clafoutis are usually cooked, but the cherries in this one weren't), topped with a fist-sized puff of white cotton candy. At the table, the waiter poured fresh cherry juice over the cotton candy, which immediately melted away to sweeten the juice into a sauce.

So there we were, faced with, count 'em, sixteen plates of dessert, all on the table at once (together with two candles, a vase with one flower, and a sheet-metal sculpture, none of which, thankfully, we were expected to eat). The waiter described each as it was placed on the table, but as you've probably noticed from my rather vague descriptions of some of them, it was hard to keep track and remember what each sauce, sorbet, and foam was made of. But we gamely set about sampling. Of my desserts, the clafouti was definitely the best, although the fresh berries in gel ran it a close second, and the pistachio tube was delicious. David liked the chocolate cylinder and the white chocolate thing. I'm not sure he ever got to the coke sorbet. The rhubarb/peach/orange/cookie thing was frighteningly horrible. Perhaps I should have tasted it first, before the others. It tasted like orange juice right after you've brushed your teeth—nastily and lingeringly bitter. And it continued throughout the rest of dessert to snap, crackle, and pop in sinister fashion, periodically spattering my right forearm with drops of the pink liquid. I wish I'd had the waiter repeat what was in it, all of which I didn't catch. I shudder to think what strange chemical reactions were taking place.

In the lobby, we were presented with another "small parting gift," this time a large sugared bioche, which David ate for breakfast the next morning.

All in all, I think l'Assiette Champenoise won the competition hands down on this occasion (except for that one awful dessert, everything was delicious, original, and intriguing (if a little silly in places). To be fair, though, we should reserve judgement until we've ordered a tasting menu at Château les Crayères, rather than a roast.

previous entry

List of Entries

next entry

Dessert

Monday morning, David still didn't feel 100%, and in addition he needed to practice his invited talk for the crustacean meetings in Texas next week, so he stayed in while I did the walking tour of the town (or part of it; you could spend hours). It covered many of the same things and places as the train tour, but it went into much more detail and allowed time and space for photography. Here's the plaque commemorating the 500th anniverary of Joan of Arc's success. It's outside a fine old half-timbered house that's now a museum of life in the middle ages (unfortuantely closed on Mondays; in fact, most of the museums were closed on Sunday and/or Monday, the only days we had in Reims).

Monday morning, David still didn't feel 100%, and in addition he needed to practice his invited talk for the crustacean meetings in Texas next week, so he stayed in while I did the walking tour of the town (or part of it; you could spend hours). It covered many of the same things and places as the train tour, but it went into much more detail and allowed time and space for photography. Here's the plaque commemorating the 500th anniverary of Joan of Arc's success. It's outside a fine old half-timbered house that's now a museum of life in the middle ages (unfortuantely closed on Mondays; in fact, most of the museums were closed on Sunday and/or Monday, the only days we had in Reims).

.jpg) The Carnegie library, considered the finest Art Deco building in Reims, is semicircular, with the entrance on the flat side. A bust of Andy himself stands before the door, which is decorated with mosaics.

The Carnegie library, considered the finest Art Deco building in Reims, is semicircular, with the entrance on the flat side. A bust of Andy himself stands before the door, which is decorated with mosaics.

A particularly magnificent building is the original headquarters of Mumm champagnes. Its huge round doorway mimics the end of a wine barrel, and the enormous mosaics across the top show the stages of champagne making. Mumm has since moved out to the edge of town, where there's more space. I forget who's in the building now.

A particularly magnificent building is the original headquarters of Mumm champagnes. Its huge round doorway mimics the end of a wine barrel, and the enormous mosaics across the top show the stages of champagne making. Mumm has since moved out to the edge of town, where there's more space. I forget who's in the building now.

In the middle of town stands the Hotel de Ville (town hall), on its own open square and adorned over the door with this relief of Louis XIII, labeled with a plaque explaining what a good, just, powerful, and generally terrific king he was.

In the middle of town stands the Hotel de Ville (town hall), on its own open square and adorned over the door with this relief of Louis XIII, labeled with a plaque explaining what a good, just, powerful, and generally terrific king he was. I haven't mentioned half of what the tour covered, just in the half of the tour I had time for! There's a lot to see and do in Reims. On the way back to the tourism office to turn in the audioguide, I passed this particularly splended patisserie window. After turning in the guide, I bought myself a doner kabab to go (a little like a gyro), with fries, and got David a ham sandwich (something simple, at his request), and we picknicked in the hotel room before meeting our vinyard-tour guide at the door of the hotel. Because we were the only people who signed up that afternoon, we not only got to pick the language, she offered to come to the hotel rather than the usual gathering place behind the cathedral.

I haven't mentioned half of what the tour covered, just in the half of the tour I had time for! There's a lot to see and do in Reims. On the way back to the tourism office to turn in the audioguide, I passed this particularly splended patisserie window. After turning in the guide, I bought myself a doner kabab to go (a little like a gyro), with fries, and got David a ham sandwich (something simple, at his request), and we picknicked in the hotel room before meeting our vinyard-tour guide at the door of the hotel. Because we were the only people who signed up that afternoon, we not only got to pick the language, she offered to come to the hotel rather than the usual gathering place behind the cathedral. The tour was great. Catherine is a young Russian woman who came to France for a year to learn the language, fell in love with and married a local wine-grower, and stayed on permanently. (She also travelled in Italy and the U.S. to learn Italian and English, both of which she speaks very well.) She's been in France for 7 years now, and they have a 3-year-old daughter who's in preschool (in France, children can start free public school at age 2; if the parents opt instead for a nanny, the state reimburses a part of the cost). When no one signs up for the tour, Catherine helps her husband in the vinyards. She hopes to get French citizenship in one more year. This is her first year giving winery tours; she used to work as a tour guide for Mumm, but she noticed an unmet demand for tours of the vinyards themselves and started her own business.

The tour was great. Catherine is a young Russian woman who came to France for a year to learn the language, fell in love with and married a local wine-grower, and stayed on permanently. (She also travelled in Italy and the U.S. to learn Italian and English, both of which she speaks very well.) She's been in France for 7 years now, and they have a 3-year-old daughter who's in preschool (in France, children can start free public school at age 2; if the parents opt instead for a nanny, the state reimburses a part of the cost). When no one signs up for the tour, Catherine helps her husband in the vinyards. She hopes to get French citizenship in one more year. This is her first year giving winery tours; she used to work as a tour guide for Mumm, but she noticed an unmet demand for tours of the vinyards themselves and started her own business. We visited vinyards of each of the three wine varieties used for champagne: pinot noir, which is trained horizontally on trellis wires; chardonnay, which is very fragile

and is therefore trained upright so that the vines aren't bent so sharply; and pinot meunier (literally "miller's pinot"), also trained horizontally, which gets its name from the tiny white hairs that cover its new shoots, giving them a "floury" look. You can see the effect in the photo.

We visited vinyards of each of the three wine varieties used for champagne: pinot noir, which is trained horizontally on trellis wires; chardonnay, which is very fragile

and is therefore trained upright so that the vines aren't bent so sharply; and pinot meunier (literally "miller's pinot"), also trained horizontally, which gets its name from the tiny white hairs that cover its new shoots, giving them a "floury" look. You can see the effect in the photo. Of course, training the vines another four buds sideways along the wires every year can't go on forever; in three or four years, each vine runs into its neighbor, and they start shading each other. So every 3-4 years, the vines are cut back to the stumps and start the horizontal training process over again. Every 30-35 years, they're torn out altogether and replaced with new ones (cuttings grafted onto Phylloxera-resistant American rootstocks), because the grapes' acidity declines with increasing vine age, and you need high acid content to make champagne. Grapes from old vines are used only in pink champagne, because the skins are more strongly pigmented. The photo shows a plot of old pinot noir vines maintained by Veuve Cliquot both for pink champagne and as a source of cuttings for new plantings.

Of course, training the vines another four buds sideways along the wires every year can't go on forever; in three or four years, each vine runs into its neighbor, and they start shading each other. So every 3-4 years, the vines are cut back to the stumps and start the horizontal training process over again. Every 30-35 years, they're torn out altogether and replaced with new ones (cuttings grafted onto Phylloxera-resistant American rootstocks), because the grapes' acidity declines with increasing vine age, and you need high acid content to make champagne. Grapes from old vines are used only in pink champagne, because the skins are more strongly pigmented. The photo shows a plot of old pinot noir vines maintained by Veuve Cliquot both for pink champagne and as a source of cuttings for new plantings. Up near the top of a hill, Catherine pointed out the large, brightly colored plastic bags tied onto frames at the ends of vinyard rows, each bearing a large number "8." She explained that, on hillsides that steep, the tractors are too top-heavy, so the annual spraying is done by helicopter. The "8" means "due to be sprayed in 2008" and the color and design of the bag corresponds to the helicopter company. Strolling around admiring the view, the birds, the vinyards, and the wildflowers, we viewed this chalk bank. The pine twig provides scale, and the pine's roots illustrate the way the vine's roots penetrate the chalk, following and enlarging tiny cracks and crevices. We also spotted a patch of dull olive-green soil, which we assumed had been sprayed with something to make it that color, but Catherine assured us that that's the natural color of clay in this region! There on the hill, with the vinyards in the background, she dressed us up in native costume and took our picture, David in his cloth cap and blue apron and me in my apron and sun bonnet—champagne gothic.

Up near the top of a hill, Catherine pointed out the large, brightly colored plastic bags tied onto frames at the ends of vinyard rows, each bearing a large number "8." She explained that, on hillsides that steep, the tractors are too top-heavy, so the annual spraying is done by helicopter. The "8" means "due to be sprayed in 2008" and the color and design of the bag corresponds to the helicopter company. Strolling around admiring the view, the birds, the vinyards, and the wildflowers, we viewed this chalk bank. The pine twig provides scale, and the pine's roots illustrate the way the vine's roots penetrate the chalk, following and enlarging tiny cracks and crevices. We also spotted a patch of dull olive-green soil, which we assumed had been sprayed with something to make it that color, but Catherine assured us that that's the natural color of clay in this region! There on the hill, with the vinyards in the background, she dressed us up in native costume and took our picture, David in his cloth cap and blue apron and me in my apron and sun bonnet—champagne gothic. Finally, Catherine took us to another little village, Coulommes-La-Montagnes (dotted, as usual, with signs pointing in all directions to champagne houses), to visit a small champagne house, Ponson Père et Fils (Ponson Father and Son), that she has a standing arrangement with. It's an example of one that does everyting; they grow their own grapes, of all three varieties, then produce and sell their own champagne. They have their own equipment for most of the steps, but for the bottling step, they employ an itinerant bottling plant that travels around the region in a truck, working for different makers by appointment. Keeping the touchy workings and fiddly adjustments of a mechanical bottling line tuned and humming isn't easy, especially when you only need it three days a year, so the smaller makers bring in the specialists for that one step.

Finally, Catherine took us to another little village, Coulommes-La-Montagnes (dotted, as usual, with signs pointing in all directions to champagne houses), to visit a small champagne house, Ponson Père et Fils (Ponson Father and Son), that she has a standing arrangement with. It's an example of one that does everyting; they grow their own grapes, of all three varieties, then produce and sell their own champagne. They have their own equipment for most of the steps, but for the bottling step, they employ an itinerant bottling plant that travels around the region in a truck, working for different makers by appointment. Keeping the touchy workings and fiddly adjustments of a mechanical bottling line tuned and humming isn't easy, especially when you only need it three days a year, so the smaller makers bring in the specialists for that one step.  The tour ended, of course, with a tasting, and David was delighted with the champagne, pronouncing it more to his taste than Moët-et-Chandon's Brut Imperial, hitherto his gold standard. Very toasty, apparently. So I, of course, asked "but will we be able to buy it in Tallahassee?" No, Catherine assured us; you can't even buy it in Reims. It's sold only right there, out the door of the building where it's made. That's got to be what some of those negociants and buyers are doing, driving around the countryside on behalf of restaurants and wine merchants, acquiring the products of these small, but very special, producers.

The tour ended, of course, with a tasting, and David was delighted with the champagne, pronouncing it more to his taste than Moët-et-Chandon's Brut Imperial, hitherto his gold standard. Very toasty, apparently. So I, of course, asked "but will we be able to buy it in Tallahassee?" No, Catherine assured us; you can't even buy it in Reims. It's sold only right there, out the door of the building where it's made. That's got to be what some of those negociants and buyers are doing, driving around the countryside on behalf of restaurants and wine merchants, acquiring the products of these small, but very special, producers. This place and the restaurant from the previous night are both GM 17/20, the two top chefs in the city, and clearly strong cross-town rivals. Once again, the table was set with both sweet and demi-sel butter, this time topped by a little label bearing the chef's name (as was, it turned out, just about anything in the place that could be labeled). The menu was deceptively simple; you can see all of it right there in the photo.

This place and the restaurant from the previous night are both GM 17/20, the two top chefs in the city, and clearly strong cross-town rivals. Once again, the table was set with both sweet and demi-sel butter, this time topped by a little label bearing the chef's name (as was, it turned out, just about anything in the place that could be labeled). The menu was deceptively simple; you can see all of it right there in the photo. Amuse-bouche 2: Vegetables, mainly thinly sliced carrots but a few others as well "en escabeche" (sort of a vegetable seviche) topped with orange mousse so fragile and insubstantial that it shimmied on the spoon.

Amuse-bouche 2: Vegetables, mainly thinly sliced carrots but a few others as well "en escabeche" (sort of a vegetable seviche) topped with orange mousse so fragile and insubstantial that it shimmied on the spoon. First course: Three variations on tomato: a room-temperature tomato tart with a veritable vegetable garden on top (the dark bits are eggplant, and a bit of artichoke and some asparagus ar lurking behind the mushroom), tomato ice cream/gaspacho with pesto and red piquillo chiles, and cube-shaped tomato cromesquis served in a paper cone standing in a tall conical dish of rock salt. All three were esquisite.

First course: Three variations on tomato: a room-temperature tomato tart with a veritable vegetable garden on top (the dark bits are eggplant, and a bit of artichoke and some asparagus ar lurking behind the mushroom), tomato ice cream/gaspacho with pesto and red piquillo chiles, and cube-shaped tomato cromesquis served in a paper cone standing in a tall conical dish of rock salt. All three were esquisite. Second course: Daurade royale (roasted "sur la plancha," i.e., on a very hot surface) with both emulsified and whole summer cocos (fresh white beans) and a chorizo mousse. Everyone seems to be serving chorizo with fish these days, but it works surprisingly well. The waiter spooned a dollop of the mousse into each bowl, then left the sauceboat in case we wanted more.

Second course: Daurade royale (roasted "sur la plancha," i.e., on a very hot surface) with both emulsified and whole summer cocos (fresh white beans) and a chorizo mousse. Everyone seems to be serving chorizo with fish these days, but it works surprisingly well. The waiter spooned a dollop of the mousse into each bowl, then left the sauceboat in case we wanted more.