More on Plougonvelin

posted 11 July 2005

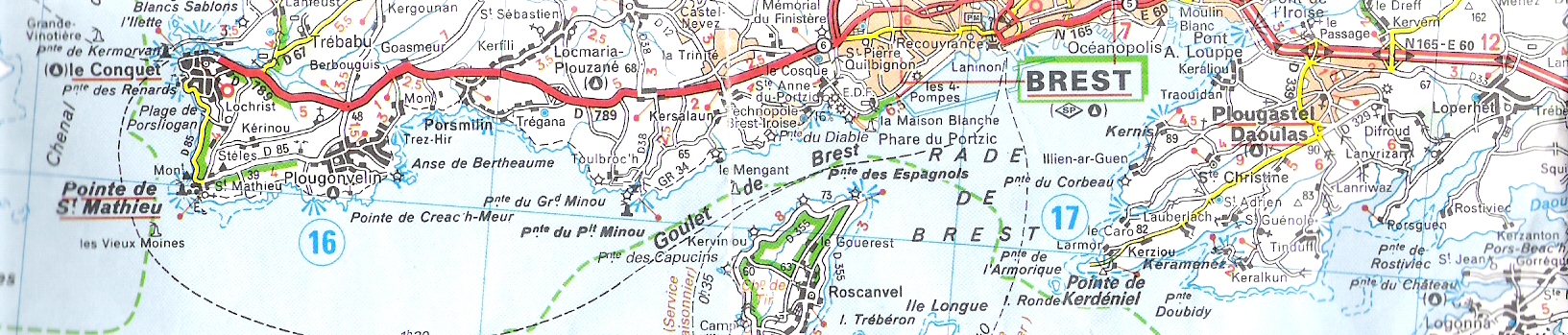

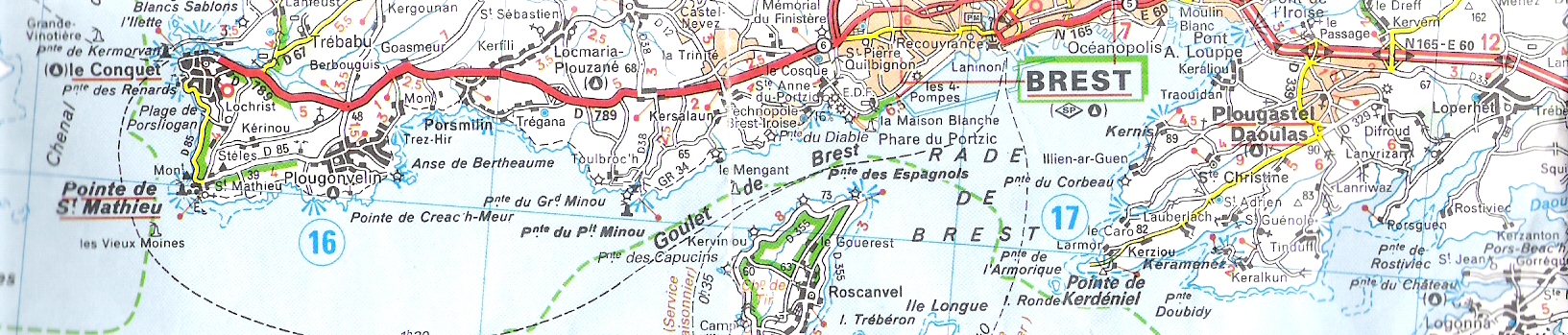

Plougonvelin is about 20 km west of Brest and about 16 km west of the Ifremer lab, which is located at Pointe du Diable ("Devil's Point"). To find Plougonvelin on this rather fuzzy map, look just above the circled blue "16." Our house was just at the top of the first "o" of "Pougonvelin." To locate other points of interest, find the words "Goulet de Brest," which are written just above one of the gracefully curving dotted lines (ferry routes). Just below those words is the peninsula terminating in Pointe des Espagnols (all the green shading indicates that all the roads are officially scenic, and the French are very strict about that designation). Just above the word "Brest" (in "Goulet de Brest") you can make out the word "Diable," marking the point where the Ifremer lab is located. Note that it, too, is considered scenic. (The view of the lab from Pointe des Espagnoles is in the June 6 entry.) Just above and a little west of "Goulet" is the Pointe du Minou, which shelters a popular surfing beach and is home to a restaurant called "1001 Lunes" (about which more later).

Plougonvelin is about 20 km west of Brest and about 16 km west of the Ifremer lab, which is located at Pointe du Diable ("Devil's Point"). To find Plougonvelin on this rather fuzzy map, look just above the circled blue "16." Our house was just at the top of the first "o" of "Pougonvelin." To locate other points of interest, find the words "Goulet de Brest," which are written just above one of the gracefully curving dotted lines (ferry routes). Just below those words is the peninsula terminating in Pointe des Espagnols (all the green shading indicates that all the roads are officially scenic, and the French are very strict about that designation). Just above the word "Brest" (in "Goulet de Brest") you can make out the word "Diable," marking the point where the Ifremer lab is located. Note that it, too, is considered scenic. (The view of the lab from Pointe des Espagnoles is in the June 6 entry.) Just above and a little west of "Goulet" is the Pointe du Minou, which shelters a popular surfing beach and is home to a restaurant called "1001 Lunes" (about which more later).

Plougonvelin is a one-flower "ville fleurie" (a flowered town); I'm not sure who awards the designations, but French towns and villages go to a lot of trouble to earn them. The award includes the right to display a large ""Ville Fleurie" sign at the edge of town, and the signpost itself includes several hooks and flanges for the display of planters full of flowers. I think the one-flower ranking must just refer the size of the village, because, square meter for square meter, Plougonvelin is way flowerier than, say, Brest, which is a four-flower ville fleurie. (It's also a four-monkey "ville internet"; the French call the "at" sign in e-mail addresses a "monkey"; Plougonvelin is apparently not especially wired).

Plougonvelin is a one-flower "ville fleurie" (a flowered town); I'm not sure who awards the designations, but French towns and villages go to a lot of trouble to earn them. The award includes the right to display a large ""Ville Fleurie" sign at the edge of town, and the signpost itself includes several hooks and flanges for the display of planters full of flowers. I think the one-flower ranking must just refer the size of the village, because, square meter for square meter, Plougonvelin is way flowerier than, say, Brest, which is a four-flower ville fleurie. (It's also a four-monkey "ville internet"; the French call the "at" sign in e-mail addresses a "monkey"; Plougonvelin is apparently not especially wired).

We noticed the lovely plantings in peoples' yards when we arrived. Rock walls double as planters. In fact, some "walls" are in fact just vertical planters, as I discovered when I saw one under construction. Rocks, from fist-sized to beachball-sized, were piled into a three-foot windrow, soil and some peat were casually scooped into the interstices, the whole think was covered with big sheets of tough green woven-plastic fabric, holes were punched in the fabric, and plants were "planted" in (more like thrust into) the holes. By the end of the season, one will see only a long mound of flowering plants. As the season progressed, though, it became clear that somebody—probably the city council—spends a bundle every year to ensure that the place is properly "flowered." The large iron hooks all over the facade of the stone church, which we had speculated were there to hold banners during religious festivals, turned out to be supports for planters. Large, municipal planters and window boxes, ready-planted with a widely varied mix of flowering annuals, started appearing everywhere, on the facade of the church; along the tops of all the retaining walls (in one case, the builders had to put them aside again for a few days, because they hadn't finished applying stucco to the wall); on the facades of all the buildings facing the main streets; hanging from every lamppost; on the porches of the post office, library, day-care center, and schools; along the edges of any sidewalk wide enough to accommodate them. All the flower beds around the church and city hall were dug up and replanted. Unobtrusive little green tubes provided drip irrigation to most. It was impressive! Maybe they're bucking for two flowers.

The stone tower of the church, which leaned every so slightly to leeward, was typical of Breton church towers. I don't know how to describe what made them so characteristic—every one is different (Plougonvelin's is among the less ornate), yet they are definitely all a type and very different from those we've seen elsewhere in France. They're carved of granite rather than sandstone, and you can usually see right through them. The bells in the one in Plougonvelin chimed the hour and the quarters, quite accurately, even though the clock on the north face of the tower had no clue. As I walked to the bakery in the morning, I would often pass by as the bells chimed 7:15 a.m., whereas the clock might say, e.g., 10:30, or maybe 4:43. This photo was taken from the south side before the planters went up. The house with blue shutters pictured above (also before the appearance of the planters) is the one you can see at the lower left in the photo of the church.

The stone tower of the church, which leaned every so slightly to leeward, was typical of Breton church towers. I don't know how to describe what made them so characteristic—every one is different (Plougonvelin's is among the less ornate), yet they are definitely all a type and very different from those we've seen elsewhere in France. They're carved of granite rather than sandstone, and you can usually see right through them. The bells in the one in Plougonvelin chimed the hour and the quarters, quite accurately, even though the clock on the north face of the tower had no clue. As I walked to the bakery in the morning, I would often pass by as the bells chimed 7:15 a.m., whereas the clock might say, e.g., 10:30, or maybe 4:43. This photo was taken from the south side before the planters went up. The house with blue shutters pictured above (also before the appearance of the planters) is the one you can see at the lower left in the photo of the church.

Plougonvelin's three tourist attractions are (1) "Treziroise," an indoor water park down in Plougonvelin Beach featuring several heated seawater pools and a giant water slide that, in places, loops out through the wall of the building over the street, then back inside again ("Unique en Bretagne!"); (2) the Fort de Bertheaume; and (3) the Pointe St. Mathieu. We didn't try the first, but the other two are both well worth visiting.

We never managed to show up at a timewhen the Fort de Berteaume was open for visitors, but we walked the perimeter of its land-side fortifications—the actual fort is on a tiny island linked to the mainland by two little bridges and an even tinier island. It's very famous and highly photogenic, so you can find many images of it by going to Google Images and searching on "fort de bertheaume."

The Pointe St. Mathieu is even more famous. It is the westernmost point in France, perhaps in continental Europe— land's send, pen ar bed, finisterre, the end of the world. It's a wild, desolate, windy, and storm-lashed place, but you can't call it Godforsaken because, as is usual in the world's most deserted places, monks showed up (in the 11th century, I think) and built a magnificent abbey there, right at the edge of the cliff. This was before the days when national parks could be instituted to prevent that kind of thing. The abbey prospered for many hundred years, although the number of monks dwindled until it was down to just half a dozen. Finally, in the 18th century, when France was feeling generally revolutionary, the locals (peasants and prosperous merchants alike) did the math and realized that those last few monks were still collecting tithes from quite a large area including a couple of thriving seaports, and living large, although to the glory of God. They threw the monks out into the road.

Nowadays, the ruins of the abbey; its accompanying museum; an old church; a "classic" tall, cylindrical red-and-white lighthouse; and a more modern, square control-tower type building from which shipping is controlled are all crowded together on the point. A couple hundred yards away is a tall cenotaph commemorating French sailors who died for their country and its small museum (again, we never caught it open). Across the road are a few houses and the Hostellerie de la Pointe Saint Mathieu, which boasts the best restaurant nearby (we ate very well there, twice; the hotel's web site, at www.pointe-saint-mathieu.com includes a lovely aerial view of the point and its buildings—in their photo, the hotel/restaurant is the white building just to the right of the red part of the lighthouse). The volume of shipping that passes by within sight of land there is staggering—something like 700,000 vessels a year these days, so when it isn't foggy, you can sit there with binoculars watching ships go by all day. (Of course, it's usually foggy. Brittany is the only place I've ever encountered wind-driven fog; on many mornings, we would open the shutters to find fog not so much blanketing the dooryard as rushing through it at 15 knots.) Again, the internet is littered with pictures of the abbey and the lighthouse; just Google (images) "pointe saint mathieu." Our photo of the lighthouse, church, and abbey is on the "Busy, busy . . ." page; the control tower is hidden behind the abbey.

In driving around the area, we discovered another vestige of the fierce battles fought in Brittany in the 1940's. On the gates of many, perhaps most, of the village cemeteries in the area is a little plaque that just says, in English, "commonwealth war graves." It signals that somewhere in the cemetery you'll find a small cluster of stones of a uniform design that mark the graves of a few British or other commonwealth soldiers, typically the crew of a bomber that crashed nearby. Great Britain has a special commission that periodically visits such graves all over the world to ensure that they are well maintained, but we invariably found them recently decorated with flowers, ribbons, or French flags, clearly by local people. These are the same villages where the war memorials all include a separate column of civilians killed by the bombardments, mostly the allied bombardments. We were touched to see that these graves are still treated with gratitude rather than bitter resentment.

Just as town names in the area tend to begin with "Plou-," meaning "parish," the names of smaller places—villages, crossroads, individual farmsteads—tend to begin with "Ker-," meaning "house." The local wine store was "Cave de Keruzas," a nearby village is "Kerjean," etc. (I never realized that the Kerguelen islands must have been discovered by Bretons until I saw the place and family name "Kerguelen" all over Finisterre.) Small roads and tracks that lead off in all directions from the already-small secondary roads are usually signposted with little black signs directing the traveller to from one to a dozen or so places, all beginning with "Ker-."

Our favorite signs, though, were those advertising local events, festivals, and whatnot—the season was just getting into full swing when we left, and we were sorry to miss the pig festival, the strawberry festival, and all the many little festivals and "kermesses" staged by villages and schools. We've often been in France for the national music festival, which is held every year on 21 June. Almost every municipality does something fairly major, and the smaller towns tend to hold theirs a few days early so that everyone can also go to the really big celebrations in the cities. Plougonvelin erected a huge banner proclaiming the date of its music festival, but for some reason—confusion or disagreement about the date or perhaps just recycling of last year's sign—we couldn't make out the date. It looked as though it had said "19" June but then someone had filled in the circle to change it to either "10" or "19" June; we couldn't tell which. Nothing happened on 10 June, so that wasn't it, but we had to leave on the morning of 18 June, so we never found out when it really was.

Our favorite signs, though, were those advertising local events, festivals, and whatnot—the season was just getting into full swing when we left, and we were sorry to miss the pig festival, the strawberry festival, and all the many little festivals and "kermesses" staged by villages and schools. We've often been in France for the national music festival, which is held every year on 21 June. Almost every municipality does something fairly major, and the smaller towns tend to hold theirs a few days early so that everyone can also go to the really big celebrations in the cities. Plougonvelin erected a huge banner proclaiming the date of its music festival, but for some reason—confusion or disagreement about the date or perhaps just recycling of last year's sign—we couldn't make out the date. It looked as though it had said "19" June but then someone had filled in the circle to change it to either "10" or "19" June; we couldn't tell which. Nothing happened on 10 June, so that wasn't it, but we had to leave on the morning of 18 June, so we never found out when it really was.

My favorite local sign, though, was the one posted by the elementary school, actually in Locmaria-Plouzané rather than Plougonvelin, that said "Danger, school! Watch out for our children!" (nice of them to warn us about the little hoodlums).

We liked Plougonvelin a lot, and I bid it a fond farewell with this scan of the charming watercolor our bakery printed on their bags.

previous entry List of Entries next entry

Plougonvelin is about 20 km west of Brest and about 16 km west of the Ifremer lab, which is located at Pointe du Diable ("Devil's Point"). To find Plougonvelin on this rather fuzzy map, look just above the circled blue "16." Our house was just at the top of the first "o" of "Pougonvelin." To locate other points of interest, find the words "Goulet de Brest," which are written just above one of the gracefully curving dotted lines (ferry routes). Just below those words is the peninsula terminating in Pointe des Espagnols (all the green shading indicates that all the roads are officially scenic, and the French are very strict about that designation). Just above the word "Brest" (in "Goulet de Brest") you can make out the word "Diable," marking the point where the Ifremer lab is located. Note that it, too, is considered scenic. (The view of the lab from Pointe des Espagnoles is in the June 6 entry.) Just above and a little west of "Goulet" is the Pointe du Minou, which shelters a popular surfing beach and is home to a restaurant called "1001 Lunes" (about which more later).

Plougonvelin is about 20 km west of Brest and about 16 km west of the Ifremer lab, which is located at Pointe du Diable ("Devil's Point"). To find Plougonvelin on this rather fuzzy map, look just above the circled blue "16." Our house was just at the top of the first "o" of "Pougonvelin." To locate other points of interest, find the words "Goulet de Brest," which are written just above one of the gracefully curving dotted lines (ferry routes). Just below those words is the peninsula terminating in Pointe des Espagnols (all the green shading indicates that all the roads are officially scenic, and the French are very strict about that designation). Just above the word "Brest" (in "Goulet de Brest") you can make out the word "Diable," marking the point where the Ifremer lab is located. Note that it, too, is considered scenic. (The view of the lab from Pointe des Espagnoles is in the June 6 entry.) Just above and a little west of "Goulet" is the Pointe du Minou, which shelters a popular surfing beach and is home to a restaurant called "1001 Lunes" (about which more later). Plougonvelin is a one-flower "ville fleurie" (a flowered town); I'm not sure who awards the designations, but French towns and villages go to a lot of trouble to earn them. The award includes the right to display a large ""Ville Fleurie" sign at the edge of town, and the signpost itself includes several hooks and flanges for the display of planters full of flowers. I think the one-flower ranking must just refer the size of the village, because, square meter for square meter, Plougonvelin is way flowerier than, say, Brest, which is a four-flower ville fleurie. (It's also a four-monkey "ville internet"; the French call the "at" sign in e-mail addresses a "monkey"; Plougonvelin is apparently not especially wired).

Plougonvelin is a one-flower "ville fleurie" (a flowered town); I'm not sure who awards the designations, but French towns and villages go to a lot of trouble to earn them. The award includes the right to display a large ""Ville Fleurie" sign at the edge of town, and the signpost itself includes several hooks and flanges for the display of planters full of flowers. I think the one-flower ranking must just refer the size of the village, because, square meter for square meter, Plougonvelin is way flowerier than, say, Brest, which is a four-flower ville fleurie. (It's also a four-monkey "ville internet"; the French call the "at" sign in e-mail addresses a "monkey"; Plougonvelin is apparently not especially wired). The stone tower of the church, which leaned every so slightly to leeward, was typical of Breton church towers. I don't know how to describe what made them so characteristic—every one is different (Plougonvelin's is among the less ornate), yet they are definitely all a type and very different from those we've seen elsewhere in France. They're carved of granite rather than sandstone, and you can usually see right through them. The bells in the one in Plougonvelin chimed the hour and the quarters, quite accurately, even though the clock on the north face of the tower had no clue. As I walked to the bakery in the morning, I would often pass by as the bells chimed 7:15 a.m., whereas the clock might say, e.g., 10:30, or maybe 4:43. This photo was taken from the south side before the planters went up. The house with blue shutters pictured above (also before the appearance of the planters) is the one you can see at the lower left in the photo of the church.

The stone tower of the church, which leaned every so slightly to leeward, was typical of Breton church towers. I don't know how to describe what made them so characteristic—every one is different (Plougonvelin's is among the less ornate), yet they are definitely all a type and very different from those we've seen elsewhere in France. They're carved of granite rather than sandstone, and you can usually see right through them. The bells in the one in Plougonvelin chimed the hour and the quarters, quite accurately, even though the clock on the north face of the tower had no clue. As I walked to the bakery in the morning, I would often pass by as the bells chimed 7:15 a.m., whereas the clock might say, e.g., 10:30, or maybe 4:43. This photo was taken from the south side before the planters went up. The house with blue shutters pictured above (also before the appearance of the planters) is the one you can see at the lower left in the photo of the church. Our favorite signs, though, were those advertising local events, festivals, and whatnot—the season was just getting into full swing when we left, and we were sorry to miss the pig festival, the strawberry festival, and all the many little festivals and "kermesses" staged by villages and schools. We've often been in France for the national music festival, which is held every year on 21 June. Almost every municipality does something fairly major, and the smaller towns tend to hold theirs a few days early so that everyone can also go to the really big celebrations in the cities. Plougonvelin erected a huge banner proclaiming the date of its music festival, but for some reason—confusion or disagreement about the date or perhaps just recycling of last year's sign—we couldn't make out the date. It looked as though it had said "19" June but then someone had filled in the circle to change it to either "10" or "19" June; we couldn't tell which. Nothing happened on 10 June, so that wasn't it, but we had to leave on the morning of 18 June, so we never found out when it really was.

Our favorite signs, though, were those advertising local events, festivals, and whatnot—the season was just getting into full swing when we left, and we were sorry to miss the pig festival, the strawberry festival, and all the many little festivals and "kermesses" staged by villages and schools. We've often been in France for the national music festival, which is held every year on 21 June. Almost every municipality does something fairly major, and the smaller towns tend to hold theirs a few days early so that everyone can also go to the really big celebrations in the cities. Plougonvelin erected a huge banner proclaiming the date of its music festival, but for some reason—confusion or disagreement about the date or perhaps just recycling of last year's sign—we couldn't make out the date. It looked as though it had said "19" June but then someone had filled in the circle to change it to either "10" or "19" June; we couldn't tell which. Nothing happened on 10 June, so that wasn't it, but we had to leave on the morning of 18 June, so we never found out when it really was.